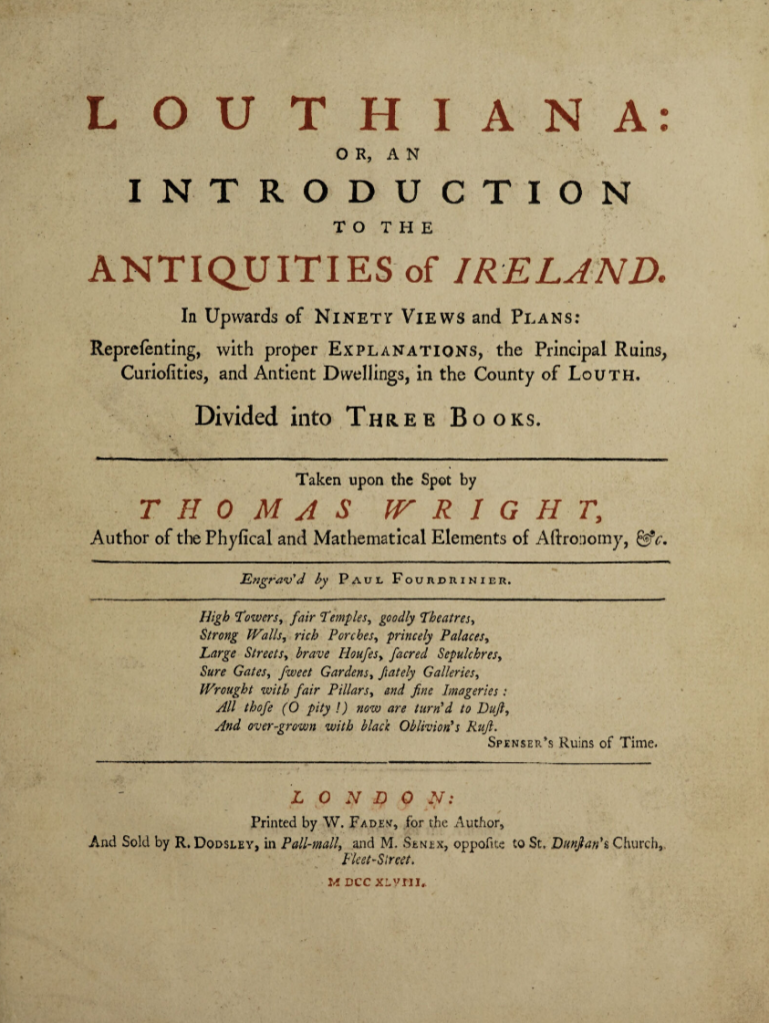

Early last year, I was on one of my usual Wikipedia dives, scrolling through a page dedicated to Barmeath Castle, a 15th-century country house a stone’s throw away from where I live. This is where I found a connection to Thomas Wright, an 18th-century English astronomer, mathematician, instrument maker, architect, and garden designer. It turns out he designed the 10 acres of gardens at Barmeath. Then I ended up reading all of Thomas Wright’s Wikipedia page, which resulted in discovering one of the projects he worked on and subsequently published called Louthiana. This is how I stumbled across the relevantly unknown work that would become both the catalyst and inspiration for this photo project.

Louthiana was written in 1746 and represents an ambitious attempt by Wright to catalogue a number of ancient/medieval stone and earth monuments across County Louth. He travelled across the county, logging all of these sites and creating detailed sketches of each one. His descriptions of the monuments and his assessment of their functions are completely obsolete. However, they do serve one very useful purpose, they give us a glimpse into what these sites may have looked like nearly 300 years ago.

Louthiana Revisited is my attempt to revisit some of the structures Wright documented with the aid of modern photography, illustrating how these sites have been altered as well as damaged over the centuries. It’s an opportunity to highlight a small fraction of the underappreciated historical sites Ireland has to offer, especially in the countryside. It’s also a chance to illustrate the differences between sites that are actively protected by the Office of Public Works (OPW) and sites that have basically been left to rot. Louthiana Revisited is a story of Ireland across centuries as well as a story of forgotten national heritage, and my own experience shooting these photographs helps to tell that story.

The wide-angle comparative photos are the main focal point of this photo project. I chose to take them this way because I felt like it would best capture the likeness of Wright’s sketches and create the true comparison that this project is looking to achieve. For the accompanying photographs, I generally took a more detailed, oriented view of specific areas of note at each site to shed some light on details that perhaps weren’t as obvious in the wider comparative photos. Lastly, many of the photo’s were touched up to create continuity in the lighting conditions throughout all the shots featured in the project.

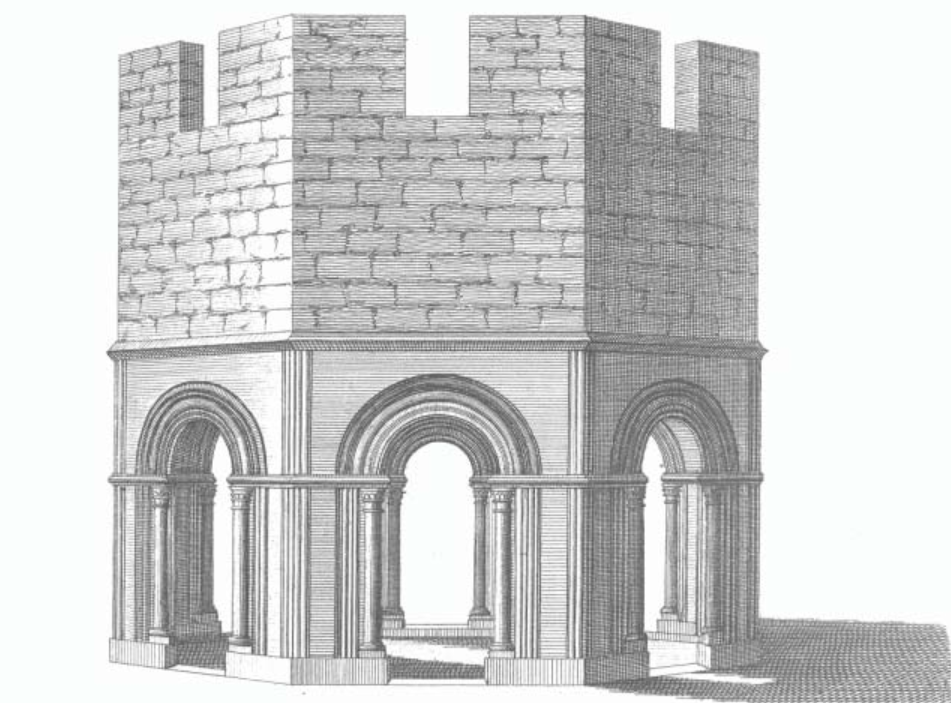

I took all the photos featured across two days with a friend giving me a hand. We started off at the Old Mellifont Abbey, the first Cistercian monastery in Ireland, founded in the 12th century. It’s a very well-maintained site, with information plaques throughout and a clear path to walk around the wider area. The lavabo itself is the centrepiece and one of the few structures still standing. A lavabo is an area for washing in a monastery, which would have been a basin full of water in the centre of the octagonal structure. The main takeaway from these pictures is the extreme deterioration of the lavabo since Wright’s visit, as well as the jaw-dropping beauty of the Romanesque architecture.

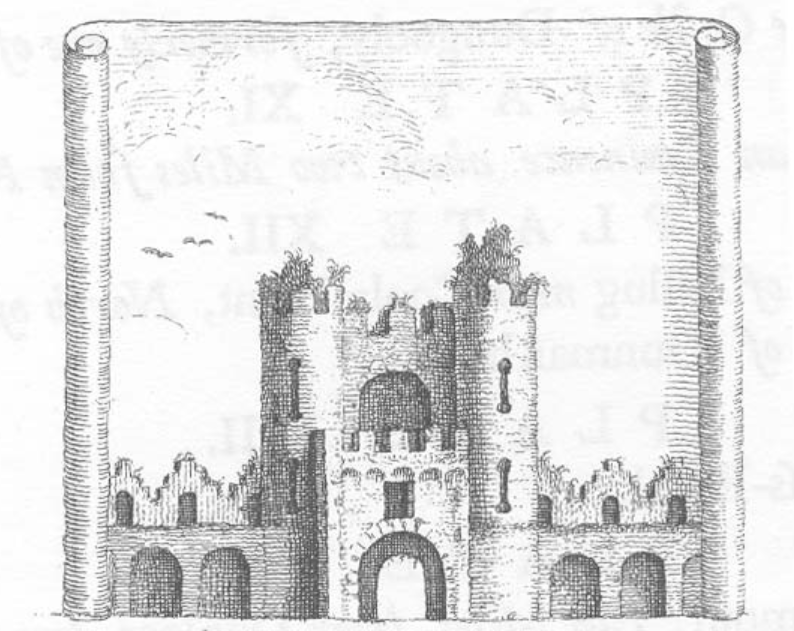

St. Laurences Gate is somewhere many people in Louth will be familiar with, being a prominent location in Drogheda, but perhaps most people have never thought too deeply into why it’s there and why it’s important. Built in the 13th century, it would have been the focal point of a set of mediaeval walls that surrounded Drogheda. Originally named the Great East Gate, the unusually high towers would have served as the ideal location to spot invasions from the sea. The most noteworthy takeaway when you compare my shot to Wright’s, is the lack of supporting walls attached to the gate. It’s incredible that the gate still stands while the walls have completely vanished over the last 300 years or more.

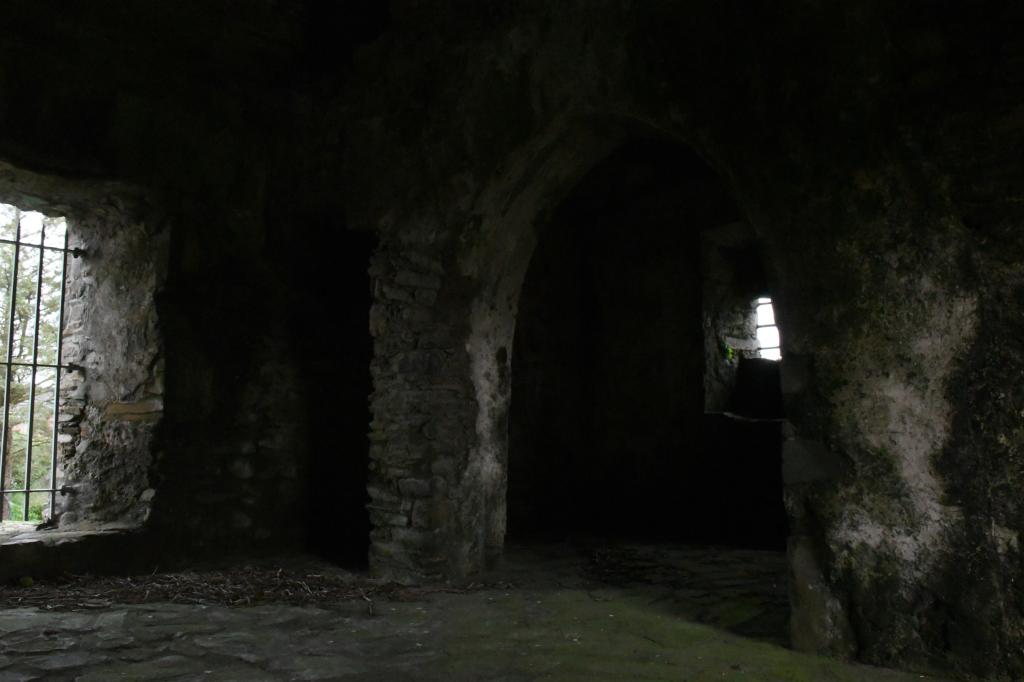

Termonfeckin Tower House was much more difficult to access. Being a lesser-known, smaller-scale structure, it was locked up when we arrived. I had to give a neighbour of the tower a ring to get my hands on the key. Then we were in; like an episode of Time Team, it felt like we were exploring an unknown piece of history, with no barriers or closed-off areas and no signage to warn us about the tight and slippy spiral staircase. Despite the extra effort it took to get inside, it was well worth it to get those dark indoor shots with the sunlight peering in. What it lacked in scale, it made up for in detail and authenticity. Being able to access the highest point in the tower was an interesting perspective, giving context as to why the tower was built in this particular location, it gives a clear view of the coast from the top.

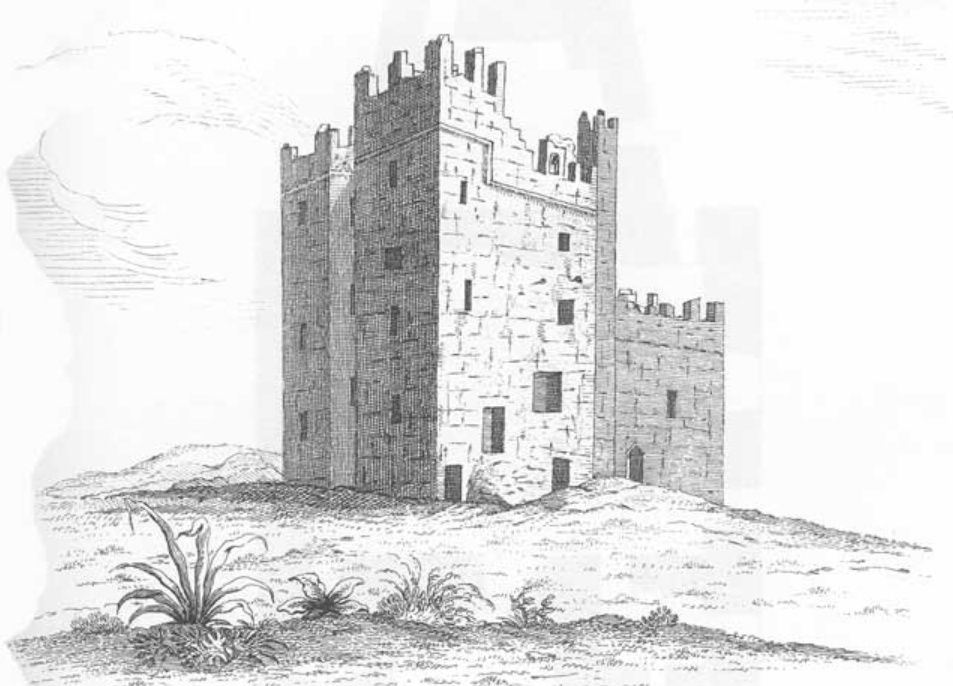

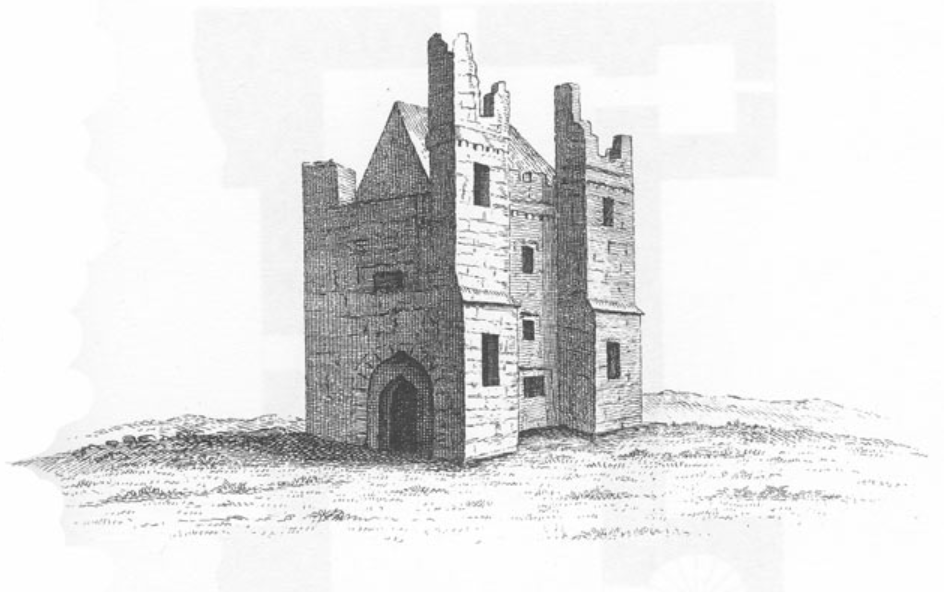

In almost completely contrasting fortunes, Roodstown Castle was nowhere near as accessible as previous locations. The most remote of all the locations we visited, it’s a beautiful 15th century, four-story tower house. Unfortunately, it was locked up behind a metal gate that I didn’t fancy trying to climb. As far as I could see from the outside, the interior of the castle was hollow, which softened the blow of not being able to explore inside. I had to compromise by getting the best angle I could from over the hedges surrounding the site, as well as getting some shots through the gate itself. It’s a stunning example of a tower house that’s clearly not accessible to the public, which I think is a huge shame.

Lastly, we visited Ardee Castle, another tower house but much bigger than the previous locations. It’s actually the biggest tower house in both Ireland and the UK. Other than its sheer size, it’s also the most altered site that we visited, with multiple visual changes over the centuries. Wright’s sketch is barren in comparison to my photo, with no other buildings in view near the castle. This could be just an artistic choice by Wright to show a clearer view of the castle, but I think it illustrates how undeveloped and rural Ireland was back in 1746.

Preface

It’s important to note that I had proposed to take a single comparative photo of each site, totalling 12 photos. At the time I wrote my proposal, I wanted to cover as many interesting sites as I possibly could, but in reality, it wasn’t possible in the time frame I had. I also felt as if it would be better to dedicate more time and photographs to each site, giving them the spotlight they deserve.

Termonfeckin Tower House

Ardee Castle

St. Laurences Gate

Roodstown Castle

Mellifont Lavabo

Leave a comment